The Science of... Socialising

- Laura Feather

- Jul 26

- 3 min read

We all experienced the dreaded years of COVID isolations and zoom socialising, and dreamt of the day we could hug our friends and family again. But what effect did those days of isolation have on our brains?

The neuroscience of socialising - wired to connect

As humans, we are inherently social, from the dawn of time we have been wired to thrive in groups as it is perceived as an evolutionary advantage.

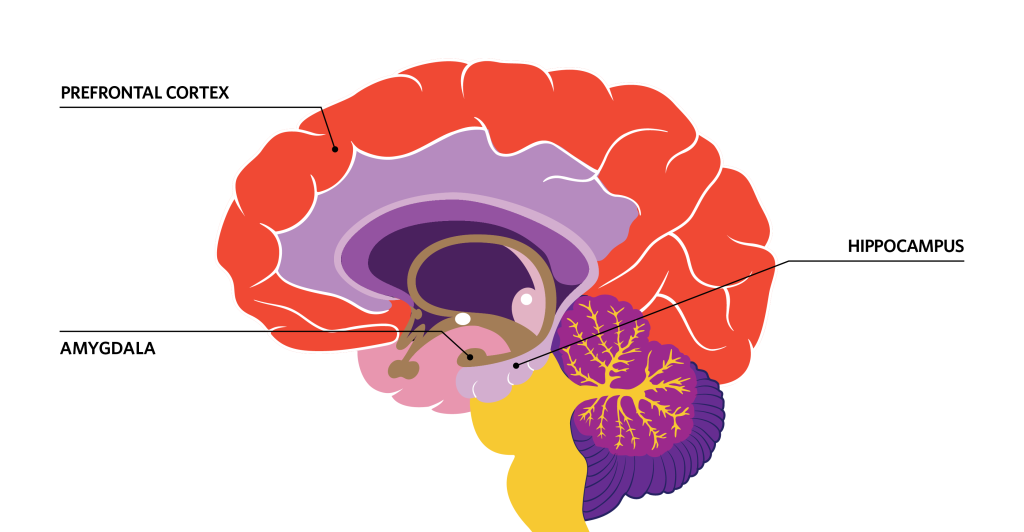

There are three regions in the brain that affect our social behaviour; the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and amygdala.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for social cognition: understanding others, interpreting facial expressions, and navigating the social dynamics of friendships and relationships (something that we all know isn't always easy!), as well as memory and decision making.

The hippocampus is the area of the brain responsible for building our social maps which helps us remember peoples faces, remember social interactions that help us navigate and adapt future interactions and works with the amygdala to help us process social emotions.

The amygdala is the area which is crucial to our emotional processing, and navigating emotional cues in social situations. It is the part of the brain responsible for our 'fight or flight' response, as it can cause fear, anxiety, and the feeling of safety. Studies have shown that the more complex social networks an individual has, the larger the amygdala!

When we engage socially, our brains release a cocktail of chemicals that act on the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and amygdala:

Oxytocin – the “bonding hormone,” which fosters trust and empathy.

Dopamine – the “reward chemical,” which makes social interactions feel good.

Serotonin – which helps regulate mood and social behaviour.

These chemicals don’t just make us feel good—they strengthen neural pathways, improve memory, and even boost immune function.

The social building blocks of development

From birth, social interaction is critical for brain development. Babies learn language, emotional regulation, and problem-solving through social play and communication.

Studies show that children who experience rich social environments tend to have higher cognitive performance, better emotional intelligence, improved communication skills, self-esteem and confidence; and stronger resilience to stress.

Even in adulthood, social learning continues to shape our brains. Lifelong social engagement with others is linked to slower cognitive decline and a lower risk of dementia.

But what happens when we’re cut off from others?

Social isolation doesn't just make us feel lonely—it’s toxic to the brain. Chronic loneliness has been linked to:

Increased risk of depression and anxiety

Higher levels of cortisol (the stress hormone)

Reduced brain volume in areas related to memory and learning (the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus)

Increased risk of dementia

It can also have detrimental impacts on other parts of our body and increase our risk of illnesses such as heart disease. Shockingly a 2020 study found that loneliness can be as harmful to health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day!

In a world increasingly dominated by screens and remote work, it’s more important than ever to prioritise real human connection. Your brain and your body will thank you!

So now that we know the importance of socialising, why not make your next social event on a rooftop in Clapham with Lit Lab events! Experience an unbeatable combination of science and sipping on cocktails in the London sun!

Sources

Around Ealing (2023). Building blocks of health - the social factors which influence health equity - Around Ealing. Available at: https://www.aroundealing.com/fighting-inequality/ealing-council-wins-5-million-research-capacity-bid/attachment/building-blocks-1080-x-1080-px-1200-x-800-px-copy/ .

Bickart, K.C., Wright, C.I., Dautoff, R.J., Dickerson, B.C., Barrett, L.F. (2011) Amygdala volume and social network size in humans. Nat Neurosci (2):163-4. doi: 10.1038/nn.2724. Epub 2010 Dec 26. Erratum in: Nat Neurosci. 2011 Sep;14(9):1217. PMID: 21186358; PMCID: PMC3079404.

Donovan N. J., Blazer, D. (2020) Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 28(12):1233-1244. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005. Epub 2020 Aug 19. PMID: 32919873; PMCID: PMC7437541.

Monash Vale Early Learning Centre - Clayton VIC. (2024). Child Care – The Importance Of Social Interaction In Early Development. Available at: https://monashvaleelc.vic.edu.au/child-care-the-importance-of-social-interaction-in-early-development-unlocking-potential/.

Novotney, A. (2019). The Risks of Social Isolation. American Psychological Association. Available at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/05/ce-corner-isolation.

Offord, C. (2020). How Social Isolation Affects the Brain | Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience | The University of Chicago. psychiatry.uchicago.edu. Available at: https://psychiatry.uchicago.edu/news/how-social-isolation-affects-brain.

US Department of Health and Human Services (2023) Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf

Find your science tribe.

Sign up to the Lit Lab London Science and Sip mailing list for the weekly blog series, 'the Science of…', Science and Sip events and experiments to try at home!

Comments